For Mario Ricci, the ethical dimension is not an abstract category; it is the very experience of existence, it is the proof of his civil and religious identity included in his artistic work.

His biographical origins that brand him proudly tuscal or perhaps it is better to say “Etruscan”, mark his countenance and features, the clear volumes of his head, and plainly show in the energetic and explicit cut of doing, at times in the “14th century novel” disposition. His is a physiognomy that has already been seen in the examples of the Roman Republican portraitists, in that undemonstrative and proud glare of the first Italian civilization, in the sanguine vis of those peoples, that could hardly avoid being in debt to the nearby Etruscans, of their realistic imprint, even in facing death.

Ricci is an aware and conscious heir to these traditions and historic essences which he externalises in the daily relations as in the imprint of his sculptural production, experienced as an extension of his thought. This is the constant dialogue that be sensed in the themes Ricci tackles, cited and summarized frequently in his treatment of the human figure. His poetic, in fact, aims at enhancing the fundamental values of the individual - at times highlighting them in a fairly authoritative manner - at speaking whit the sincere tone of Man, both through the immediacy of the figurative as well as through the hieratic quality of his abstract works.

The need to exprees whit clarity these values is captured in the graphic sketches that Ricci drafts to study his formal solutions, later used as a basis for his sculpture: the style is crisp and clean, not at all self-congratulatory and it does not dwell in descriptivism, except perhaps to place the obligatory an his overall consistency. Precisely in that case, the sculptures will reach a more effective, more direct semantic solution. And perhaps in this capacity for fusion, we again sense the background of Etruscan art, that bittersweet laughter, that broad, reflective and astute vision of the whole, of man and his life.

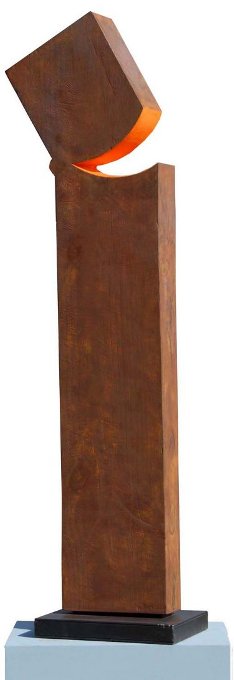

The proclivity for the sculptural language is no more than a replication of the almost categorical cut of his commitment: there is virtually no possibility to make corrections when working whit wood, perhaps this is why Ricci prefers it over other materials. He manoeuvres his chisel with a steady, determined hand, though the sculptor frequently allows himself to be guided by the sinuous rhythm of the grain of the wood, letting himself be seduced by the sensuality of the raw material.

In this way, Ricci brings to the fore the ethical and spiritual dimension of the human being, offering it to public - that of the 21st century - ever more indifferent and deaf to the deep meaning of the images that crowd the contemporary world. It is not only through the moulding of faces and bodies that Ricci deals with this theme: he does the same also in his abstract works, and thus exposes the viewer to a consistent conceptual journey. In fact, the fascinating vitality of Ricci’s later works seems to derive precisely from the sense of artistic completion that he strives to confer to infinity.

Elisabetta Doniselli